Active modes (walking, bicycling and their variants) and micromodes (e-bikes and e-scooters) can provide large climate emission reductions and other important benefits, if we let them. Small modes are important but often undercounted and undervalued.

Greetings from Washington D.C., where I am attending the 2023 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, a massive and amazing conference. It’s been wonderful to see many friends and colleagues after a two-year hiatus.

I am encouraged by what I’ve seen here. There is a lot of good research concerning subjects I care about: equitable, affordable, healthy, and sustainable transportation planning, plus improved understanding about transportation-land use relationships and the value of Smart Growth development policies that create more compact, accessible and multimodal communities.

On Monday I presented my paper, Evaluating Active and Micro Mode Emission Reduction Potentials, which examines the roles that active modes (walking, bicycling and variations such as wheelchairs and handcarts) and micro modes (e-bikes, e-scooters and variations) can play in achieving transportation emission reduction targets. My research suggests that these “small” modes can provide significant emission reductions which are undercounted and undervalued in emission reduction plans.

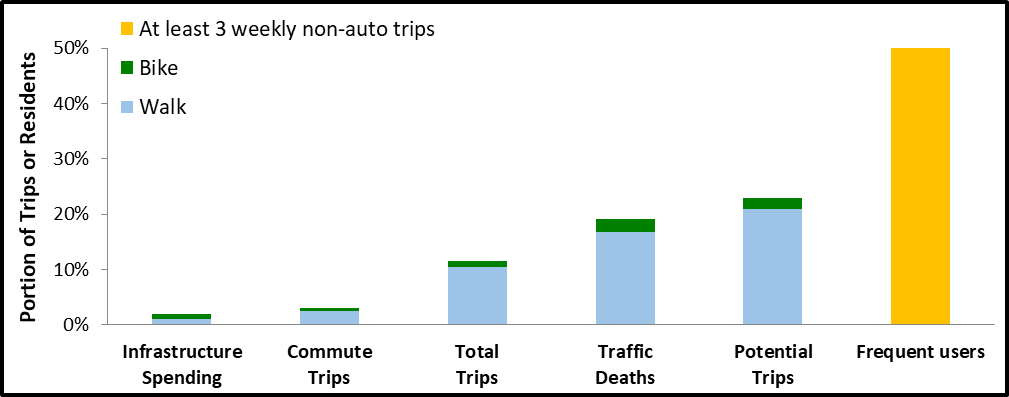

All too often, planners evaluate travel demands using census commute mode share data, which show that only 3.6% of trips are made by active and micro modes, but since this only counts the dominant mode used for travel to work, it greatly underestimates their actual share of total trips. For example, if you bike for ten minutes to a bus stop or train station, ride public transit for ten minutes, and walk ten minutes to your destination, that trip is categorized as a transit trip although you’ve spent twice as much time travelling by active modes. Surveys that account for all trips find that active modes actually serve 12-15% of trips, three times more than indicated by commute mode share data.

Another bias is the common assumption that each mile walked or biked can only replace, at best, one vehicle-mile. In fact, walking and bicycling improvements can leverage much larger vehicle travel reductions, so each additional kilometer walked or biked reduces five to ten VMT. This occurs because pedestrian and bicycling can leverage additional reductions in vehicle travel, so each mile of increased walking and bicycling reduces more than one vehicle-mile of travel. For example, walking and bicycling reduce chauffeuring trips (special trips made to transport a non-driver. Such trips usually generate empty backhauls (empty return trips) which essentially double vehicle miles of travel, and therefore the vehicle-miles reduced when non-drivers can travel independently. Small modes also support public transit travel, encourage more compact development, and help households reduce their vehicle ownership, all of which help leverage large vehicle travel reductions.

Because e-bikes can easily travel longer distances, carry larger loads, and climb steeper inclines pedal bikes they greatly increase the amount of automobile travel that can be reduced, so if conventional models predict that active modes can reduce 10% of vehicle travel, active and micro modes can probably reduce 20%, if they are given suitable support: improved paths and lanes, suitable parking and charging facilities, lower urban traffic speeds, TDM incentives, plus suitable purchase subsidies.

Conventional planning undervalues small modes by ignoring their many co-benefits. Improving and increasing active and micro modes reduces household costs, road and parking infrastructure costs, traffic congestion and crashes, and sprawl-related costs, in addition to reducing pollution emissions; and it also improves public fitness and health. Most transportation emission reduction plans are incorporating the same biases.

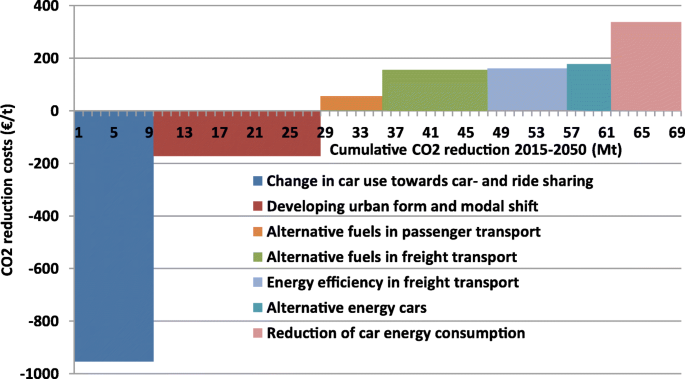

Considering all impacts, vehicle travel reduction strategies often have negative costs; their total benefits are greater than their total costs, making them no-regrets strategies that are justified regardless of their emission reduction impacts. The figure below shows the large negative costs of vehicle travel reduction strategies, compared with the relatively high costs of clean vehicles.

Emission Abatement Cost Curve (Liimatainen, Pöllänen and Viri 2018)

My review found that the majority of transportation emission reduction plans devote most of their investments to subsidizing electric cars, which isn’t bad, but provides limited benefits. If, instead of convincing a typical family to purchase an electric rather than a gasoline car emission reduction programs convinced them to purchase a fleet of pedal and electric bikes they will provide far more total benefits.

There are other good reasons to invest more in these small modes. One justification is simply fairness; most jurisdictions currently spend a much smaller portion of their transportation budget on active and micro modes than their share of current or potential trips, their share of traffic deaths, or the share of frequent users (travellers who use small modes at least three times per week). The graph below illustrates this.

For the last century transportation planning has undercounted and undervalued small modes. Will we make the same mistakes with emission reduction planning? Planners can do better! We need more comprehensive emission reduction planning.

For More Information

Torsha Bhattacharya, Kevin Mills, and Tiffany Mulally (2019), Active Transportation Transforms America: The Case for Increased Public Investment, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy.

Christian Brand, et al. (2021), “The Climate Change Mitigation Effects of Daily Active Travel in Cities," Transportation Research D, Vo. 93.

Knight Frank (2020), Walkability and Mixed Use - Making Valuable and Healthy Communities, The Prince’s Foundation.

Heikki Liimatainen, Markus Pöllänen and Riku Viri (2018), “CO2 Reduction Costs and Benefits in Transport: Socio-technical Scenarios,” European Journal of Futures Research, Vo. 6/22.

Todd Litman (2021), Evaluating Active Transport Benefits and Costs, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2023), Comprehensive Transportation Emission Reduction Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Michael McQueen, John MacArthur and Christopher Cherry (2020), “The E-Bike Potential: Estimating Regional E-bike Impacts on Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” Transportation Research D, Vo. 87.

National Parks Layoffs Will Cause Communities to Lose Billions

Thousands of essential park workers were laid off this week, just before the busy spring break season.

Retro-silient?: America’s First “Eco-burb,” The Woodlands Turns 50

A master-planned community north of Houston offers lessons on green infrastructure and resilient design, but falls short of its founder’s lofty affordability and walkability goals.

Delivering for America Plan Will Downgrade Mail Service in at Least 49.5 Percent of Zip Codes

Republican and Democrat lawmakers criticize the plan for its disproportionate negative impact on rural communities.

Test News Post 1

This is a summary

Test News Headline 46

Test for the image on the front page.

Balancing Bombs and Butterflies: How the National Guard Protects a Rare Species

The National Guard at Fort Indiantown Gap uses GIS technology and land management strategies to balance military training with conservation efforts, ensuring the survival of the rare eastern regal fritillary butterfly.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

EMC Planning Group, Inc.

Planetizen

Planetizen

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service