C.J. Gabbe guest blogs about a recent article in the Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Guest Blogger: C.J.Gabbe of Santa Clara University.

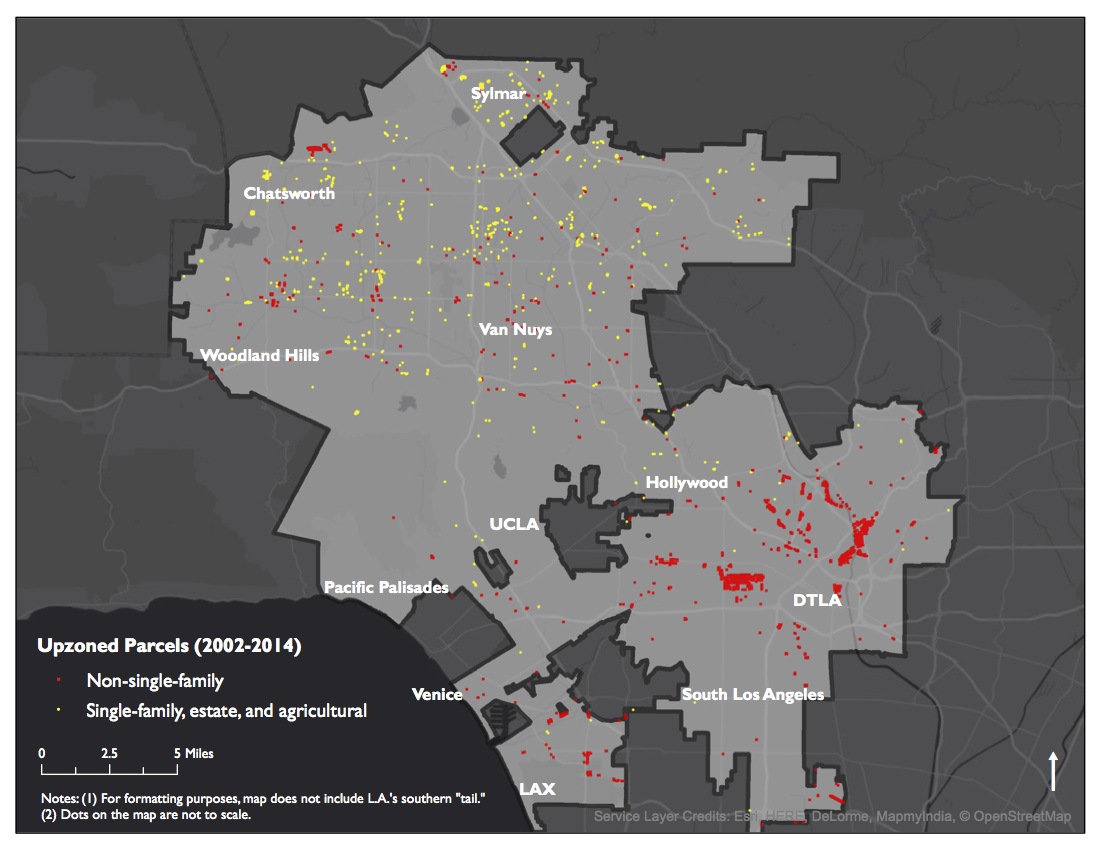

The quantity, quality, and location of new housing affects affordability, climate change, and social equity. Zoning changes that enable more housing construction ("upzoning") are often necessary and yet we have little empirical evidence about where and why rezonings occur. In a recent article in the Journal of Planning Education and Research, I examine the prevalence and characteristics of upzoning in Los Angeles.

To set up my analysis, I began by assigning every Los Angeles parcel with zoning attributes from 2002 and 2014. I flagged areas where zoning changed, and I focused on parcels where more residential development was allowed. I then developed regression models to estimate the odds that a given parcel was upzoned after 2002 based on its neighborhood amenities, regional accessibility, transit proximity, initial regulatory characteristics, environmental features, and local socioeconomic and demographic characteristics.

My research shows that upzoning was uncommon in Los Angeles. Only 1.1% of the city’s parcel land area was upzoned between 2002 and 2014. Some of this upzoning was city-initiated following adopted plans, but property owners initiated many of the upzonings. When upzoning did occur, it commonly followed a path of development opportunity combined with least political resistance.

Upzoning was most likely for parcels:

- Zoned for low-intensity uses, like parking and manufacturing.

- In neighborhoods with rising rents.

- In sections of Los Angeles with newer community plans.

Upzoning was least likely:

- In neighborhoods with larger shares of homeowners.

- Nearer to the beach.

- Close to elementary schools with higher standardized test scores.

Many American cities–like Los Angeles–will need to update their plans and approve zoning changes to achieve broad policy goals of limiting sprawl; increasing walking, biking, and transit ridership; improving access to good schools and jobs; and expanding housing supply. Based on this and related research–and my experience in planning practice–I propose four key principles for planning and regulating urban development:

- Zoning changes should follow deliberate, inclusive, and transparent planning, rather than ad hoc decision making. If a long-range planning system isn't functioning smoothly, there will be conflicts downstream about zoning and development approvals. This is Los Angeles' situation today; the city is now moving toward updating its 35 community plans.

- Cities change, and planning processes must be framed around "how to change" rather than "whether to change." Some existing residents express concerns about protecting their access to amenities and "neighborhood character." Again, my research shows that upzoning was particularly unlikely in neighborhoods with high shares of homeowners. Planners can partially mitigate these concerns by linking new development with public improvements, and through clearly written and predictably applied regulations. But, planning for growth requires political leadership, and ultimately will be a compromise for some local stakeholders.

- Citywide policy changes may be more politically feasible than piecemeal parcel- and neighborhood-scale changes. For example, a city can systematically reduce minimum parking standards near transit stations–rather than selectively in certain station areas–or allow accessory dwelling units without additional parking requirements in all single-family zones. This kind of holistic approach can reduce case-by-case decisions, even if policies are designed to account for some context-related factors.

- Sometimes state intervention is necessary to break planning and zoning logjams. State governments should intervene when restrictive municipal regulations hinder regional housing and environmental goals, particularly near major transit investments. For instance, California's density bonus incentives allow streamlined approvals, higher densities, and other regulatory relief in exchange for affordable housing provision.

In short, planning for the future may not be easy, but it shouldn't be impossible. Through proactive planning followed by zoning updates, growth can be equitable, environmentally sensitive, and meet the needs of existing and future residents.

Open Access Until May 31, 2017

Analysis: Cybertruck Fatality Rate Far Exceeds That of Ford Pinto

The Tesla Cybertruck was recalled seven times last year.

National Parks Layoffs Will Cause Communities to Lose Billions

Thousands of essential park workers were laid off this week, just before the busy spring break season.

Retro-silient?: America’s First “Eco-burb,” The Woodlands Turns 50

A master-planned community north of Houston offers lessons on green infrastructure and resilient design, but falls short of its founder’s lofty affordability and walkability goals.

Test News Post 1

This is a summary

Analysis: Cybertruck Fatality Rate Far Exceeds That of Ford Pinto

The Tesla Cybertruck was recalled seven times last year.

Test News Headline 46

Test for the image on the front page.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

EMC Planning Group, Inc.

Planetizen

Planetizen

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service